A picture may well tell a thousand words but what if that picture is tweeted, shared and liked? Could social media help engage the community with local wetlands? Could it assist in crowd sourced tracking of environmental change?

A picture may well tell a thousand words but what if that picture is tweeted, shared and liked? Could social media help engage the community with local wetlands? Could it assist in crowd sourced tracking of environmental change?

After the fire comes the photos

Using photography to track post-bushfire environmental change is common in Australia where bush fires are a part of life. Scientific publications and technical reports produced across the country have used “before and after” photos to highlight the dramatic change, and equally dramatic recovery, seen in the Australian bush after fire.

How can we incorporate social media in tracking this post-fire recovery? Perhaps it could even play a role in boosting the spirits of the local community seriously impacted by bushfire? The recovery of communities is as important as recovery of the environment. A recent study has highlighted the importance of social networks in the community and perhaps opportunities to share interactions with the environment through social media would provide further opportunities for engagement.

Bushfires are a natural part of the Australian environment and photography plays a key role in reminding us that our vegetation can respond remarkably after even the most intense fires (Source: CSIRO)

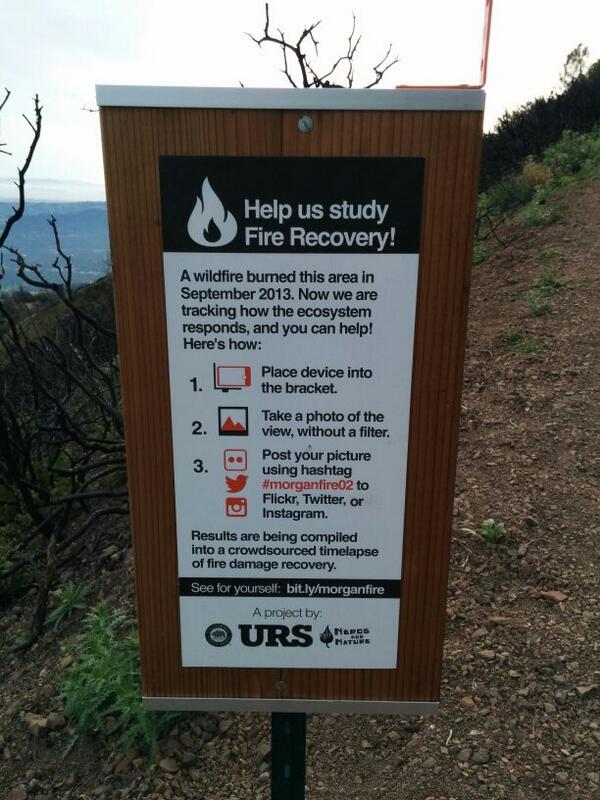

An example of engaging social media in bushfire recovery comes out of California. I’m particularly taken by the use of social media as a critical component of the program tracking recovery from bush fires that swept through Mt. Diablo in 2011. The project is coordinated by the Nerds for Nature team, inspired by the initiative of Sam Droege and his Monitor Change project.

The idea is based around members of the community taking photos at set locations with set perspectives and compiling those photographs shared through social media, to create a crowd sourced time lapse animations of post-bush fire recovery (you can read a little more about it here). What makes this so neat is the simplicity. Clear signage and a simple bracket for lining up your camera/phone. The website interface is great too. The team behind the project have provided some detailed instructions that form a great basis for adapting this approach to a local environment (they also point out that this project may not be as simple to implement as you may think…).

Tracking bushfire recovery with crowd sourced photographs! (Originally tweeted by Sergei Krupenin in reference to Nerds for Nature program)

An Australian take on crowd sourced “environmental change” photography

Another example of using photography to track environmental change is the Australian Fluker Post project. Similar to the approach by the Nerds for Nature team, this project, coordinated by Dr Martin Fluker at Victoria University, is a “citizen science system designed to allow community members to contribute towards the ongoing care of various natural environments by taking photographs”.

“Fluker Posts” are installed at key locations and members of the community can use their own cameras to take photos and then email them to coordinators. As well as collecting material to assist local land managers, this project may have a more subtle influence on conservation by engaging the community with the local environment. By providing an opportunity for local residents (as well as regular visitors) to track the changes in their local environment, it would be hoped that a connection and care for the local environment would increase. As well as directly changing behaviour that may threaten local habitats or wildlife, the community (and by extension local decision makers) are more likely to be supportive of rehabilitation efforts.

An example of a newly installed Fluker Post ready to help track environmental change (Source: The Fluker Post Project)

You can see examples of photos from the various Fluker post locations here but you can also keep up to date with various projects at the Fluker Post Facebook page. A relatively new venture has just kicked off using this “technology” to engage with school students – a great idea!

Tracking tidal changes

Another great example of crowd-sourced tracking of the potential environmental change is the Witness King Tides program. The program is coordinated by Green Cross Australia and calls of members of the community to submit photos taken during king tide events (the highest of the spring tides each month) to help generate an indication of what may happen in the future with sea level rise. There is a wonderful collection of photo albums here from across Australia.

This idea of a crowd-sourced collection of photographs tracking tidal events has been tried in the past. Most notable was a collection of photos contributed to by over 250 people taken during a major tide event in 2009. A useful document was produced by NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. It highlights an important issue in relation to potential impacts of sea level rise. The first wave of impacts may not be catastrophic but they will be disruptive.

While images of major cities underwater often accompany media reports of rising sea levels and plans for adaptive responses, in many parts of Australia, increasing frequency of these “higher than usual” tides will cause disruption to cities and townships in other ways. Blocking stormwater systems, forcing the closure of roads and delays with ferry services. In addition to this, there is the increasing risk of coastal erosion and loss of amenities in coastal regions.

“Before and after” shots of a cycleway through Sydney Olympic Park in January 2014. Higher than expected spring tides flooded many of the pathways, cycleways and boardwalks in the local area causing much disruption; perhaps a sign of things to come if rising sea levels make these event more frequent.

One of the problems with this method, however, is that these photographs end up being “one offs”. Without a comparison to “normal” conditions, it can sometimes be difficult to gauge the significance of tidal inundation without being familiar with the local area. Fortunately, there are many examples where contributors send both “before” and “after” tidal inundation shots and they do provide a stunning visual representation of the disruption sea level rise may cause. Perhaps the incorporation of “photography points” (following the examples from the Flucker Post or Nerds For Nature teams) at key locations would be a useful addition to the program?

This approach has been adopted bytThe City of Manduarh in Western Australia with their Tidal Image Mandurah Project. The community has been asked to take photos at key locations with a view that images of tidal events such as storm surges, high tide and erosion will help track change. Nothing too fancy in these locations either, just a strategically placed spray painted blue camera!

An example of the spray-painted blue camera on a beachside post inviting members of the community to take and share a photo of Florida Beach (Source: City of Mandurah)

Tracking constructed wetland change

Where would I like to see this implemented? I’ve had the opportunity to work in and around many newly constructed wetlands. These have ranged from small freshwater wetlands in urban areas to extensive rehabilitated estuarine wetlands. The common denominator across all these sites has been vegetation change. I cannot be out there every week taking photos but it would be great if there was a collection of photos being shared by the local communities that I could tap into.

There are some great examples of interpretive signage around our local wetlands. There is also a shift in thinking from traditional interpretive signage to take advantage of new technologies so why not include social media to engage visitors and local community further? Perhaps social media networking should be included in wetland management plans?

Signage at Gungahlin Wetlands, ACT. An example of structures associated with urban wetlands that can be modified to include opportunities for social media use through the use of recommended hashtags (for Twitter or Instagram) and/or brackets for placing cameras/smartphones

A simple addition of a bracket and details on sharing photographs could easily be incorporated into local signage as it is installed and/or updated. As well as tracking changes in vegetation growth in and around constructed and rehabilitated wetlands, the encroachment of mangroves into mudflats or sandy shores along urban estuaries could be a focus too. Of course, storm events and unusually high tides could be documented too. An added bonus would be if some rare or unusual wildlife popped up in photographs.

Educational signage of this nature is common place around wetlands in Sydney, could the inclusion of some guidelines for social sharing images help track mangrove incursion into shoreline habitats?

There are plenty of other ways social media can assist environmental conservation and rehabilitation. Pozible and Landcare have recently announced the launch (and called for the submission of proposals) of a new global crowdfunding partnership called The Landcare Environment Collection, an opportunity to showcase and support the crowdfunding campaigns of environmental groups in Australia and around the world.

Perhaps I need to prepare a proposal for the installation of some “social sharing” camera stands…

Why not join the conversation on Twitter and help share other examples of where social media could help track environmental change.